Cosmopolitan Magazine January 1973

|

MELANIE SINGS

IT AND ZINGS IT |

|

|

|

By: Harvey Aronson |

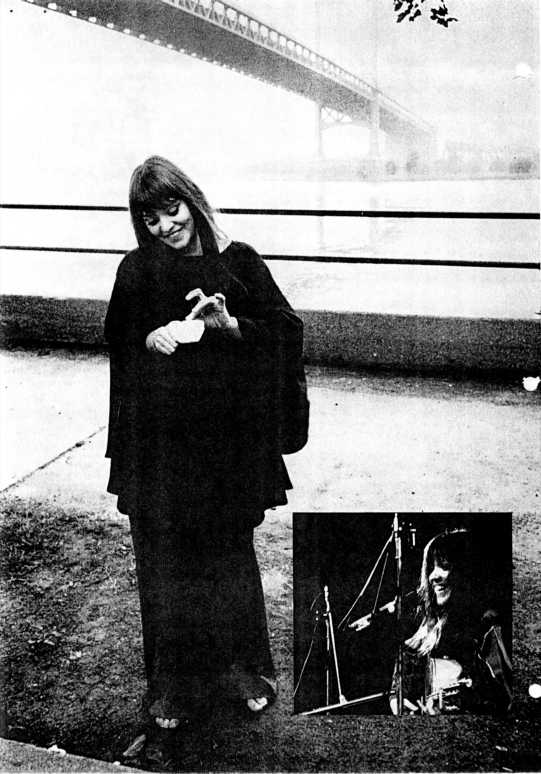

Photos by: Elliot Landy |

|

|

This high

priestess of the Vulnerable Generation holds her votive Cult in thrall. We are at Sienna, a small Catholic college near Albany, New York. Sienna has coed dorms, a lacrosse team, and a school newspaper called The Indian. And tonight, as part of Spring Weekend, it also has Melanie Safka Schekeryk, a twenty-five-year old onetime high school misfit who writes and sings songs of self and loneliness and who has become one of the high priestesses of the Vulnerable Generation. Outside thc Sienna gym, kids are gathering two hours in advance of Melanie's concert. Inside, Jerry Kellert, who helps handle the singer's schedule, is talking to a stage manager. "She doesn't need an intro," Kellert is saying. "She just walks on cold'?" says the stage manager. "Yes," says Kellert. "She just walks on cold. She's a simple acoustical act just one girl on a stage " What Kellert doesn't say is that Melanie is also quite hoarse--throat strain, an occupational hazard. Her voice had begun to bother her last week, when she was in Manhattan cutting her seventh album, a one record package titled Stone Ground Words. Earlier today, Melanie had been trying to rest out the strain in a motel room; at the moment, she is in a hospital a few miles from the campus having her throat painted. "If we're a couple of minutes late, don't worry," Kellert tells the stage manager. ' We'll be here." He turns to the student who will handle the spotlights: "Lots of pinks and reds, but don't go wild." By the time the concert starts, the gym is wall-to-wall with kids. They sprawl up against the stage and fill the side bleachers and rows of orange ard yellow chairs that line the floor beneath the girdered ceiling. A faint smell of pot permeates the room, hut most of the red tips glowing in the half-light belong to real cigarettes. A few wineskins are being passed around, and stags near the stage we drinking beer. A country-rock group pounds the gym with sound for about an hour. Then comes intermission. Now the house lights go out and a red spot softens the stage. 'This is Tom Jones," a wag in the bleachers hollers, but the laughter is drowned out by applause as Melanie comes on---cold. She has been coming on cold since she was a sixteen-year-old earning $20 a night for four straight hours of singing at a club near Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. She has also been coming up in class. In 1971 Melanie sang from the rostrum of the UN General Assembly, and recently she made a world tour for UNICEF. And wherever she goes, Melanie works at being honest. A few months before Sienna, during a concert at West Point, she told the audience, "I think a point was made by asking me here. Well, I got something to say to make the point more obvious " Then she introduced her new peace song, which begins, "Hearing the news ain't like being there . . ." and ends, "There are people who are living on the death in the land." She got a standing ovation. Tonight, Melanie sits on a straight-backed chair and starts to sing at Sienna: "Wild wild horses/ we're gonna ride them some day." Her earthy voice is huskier than usual. Kids push toward the stage popping flashbulbs, and somebody lights a candle in front of her The candle-lighting business had started some four years ago with "Candles in the Rain," a song commemorating Woodstock: "So raise the candles high/ 'Cause if you don't we could stay black against the night/ So raise them higher again/ And if you do/ We could stay dry against the rain."+ Woodstock and Powder Ridge. Places like Houston and Chicago and Richmond and Westbury. All the Sienna's in the country of the young. Melanie's terrain. For the greater part of the year, she does as many as four concerts a week. criss-crossing America with her husband, Peter Schekeryk, who is also her manager and music publisher and for whose label (Neighborhood Records) she records. If Melanie allows herself any leisure at all, it's the few times a year she escapes with a sleeping hag to a hilltop in Escondido. California ('It's a place where there are some mountains and a valley, and I can sleep out and come hack to a cabin"). But tonight those mountains must he as far f mm her thought as they are from Sienna as Melanie sings, "Wild, wild horses." She drives to a finish, and the kids roar, whistle, stomp, and applaud. As a teen-ager, Melanie had almost no friends, unless you count the thirty-five-year-old English teacher with whom she had an affair . . . one of the most pleasant memories of her girlhood. She says, "He was very good for me. It was the most comfortable relationship I'd ever had. It was much less of a nervous thing than thinking of really being open with somebody my own age, because I didn't trust kids. I just didn't trust anybody my own age. The only people I ever felt comfortable with were people much older than me." Ironically, it is people younger than she who trust almost worship—Melanie. Still, she thinks of herself as unattractive much of the time—With two major exceptions: when she's on that mountaintop, and when she's singing. "When I sing, I feel beautiful," she told me just the day before. "Sometimes, if I'm honestly doing the songs, and I'm with the words and the thoughts at the time that I'm singing them, it's, uh, kind of a light that I feel all around me. I don't know what it is, but I feel it from my insides and I can see it. When this light is there, I know that the people are getting what I'm getting. And I'm glad it's happening." My response was to make a reference to Simon and Garfunkel's "Bridge Over Troubled Waters," and the line that goes, "Sail on silver girl, your time will come to shine."# Melanie had nodded. "When I'm singing," she said, "that's my time, I guess." So here she is tonight, trying to hold on to her time in a small college gym, where the scoreboard advertises Pepsi-Cola and amplifiers are rigged atop metal stands at the sides of the stage. "I'm gonna tell you something," Melanie tells the audience. "I recorded 'Wild Horses' three keys higher last week. I've lost my voice, and what I'll do is--I'll do songs you can sing along to. If it gets too bad, I'll just leave and come hack some other time." "No, no," the kids yell hack, and so now the concert takes on a story line. "I'll try," Melanie says. "What can I do. I'll try. I'll try." And she tries with "Lay My Hands Across the Six Strings," which she has written for her new album. Melanie does not read music; she composes her songs in her head, the words and tunes often coming in a simultaneous outburst. Then she hones each new number by singing it over and over, finally putting the songs on tape, and sending it off to an arranger. Sometimes, Melanie writes the words down in her journal, a slapdash diary which also contains appointments, random thoughts, and the names of people she meets. Ask about her favourite songwriters, and she mentions Johnny Mercer, whose heyday oredates her life. She also likes Cat Stevens' work, and is mesmerised by the melody of Eric Clapton's recording of "Layla." She has read everything poet-novelist Richard Brautigan has written and is fascinated by Joan Didion's novel Play It As It Lays. Her own works ranges from the effervescent to the introspective. "Lay My Hands Across the Six Strings," which she is singing now, is in the later category: "I'm thinking sixty miles an hour in a thirty-mile zone."* As she finishes "Hands," the roar is even louder than before, and the audience begin to shout requests. A young man hands up a bottle of wine to the stage. Melanie takes a pull. "Oh, yeah," she says, and the kids' enthusiastic reaction makes you think maybe the generations are not so polarised as many people think; the laughter in the gym right now is reminiscent of the chortling of overdressed adults in Miami Beach watching Jackie Gleeson smack his lips over a booze-filled coffee cup. Except Melanie gives back the bottle. "Psychotherapy," somebody shouts, and Melanie nods. It's one of her group-participation numbers, sung to the tune of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" and parodying Freudian theory. The audience claps to the beat and joins in the refrain: "'Glory, glory psychotherapy/ 'Glory, glory sexuality/ 'Glory, glory, now we can be free/ As the id goes marching on.'" The final verse puts everything together: "Feud's mystic world of meaning needn't have us mystified/ It's really very simple what the psyche tries to hide/ A thing is a phallic symbol if it's longer than it's wide/ As the id goes marching on.'" Melanie is pushing her voice now, but the audience doesn't seem to notice. It's their time, too. "Let's see," she says, "I'm trying to think of what I can sing." "'Beautiful People,'" somebody yells, and Melanie says she'll try it. The song was her first breakthrough, almost seven years ago. Not a big hit, but big enough to generate a cultish following. And tonight, as she serenades that following, you can tell she is labouring. Coming to the line "So if you take care of me, I'll take care of you"+ she breaks off. "I can't," Melanie says. "I--I can't--I'll come back." Now the candle is burning in front of an empty chair. Melanie had been onstage only about twenty-five minutes; normally, she would have stayed for another three-quarters of an hour. Her Midsong departure is like an unexpected ending to a prize fight--as if the boxer who has been winning is suddenly disqualified on a foul. Some of the kids stand about in disbelief. Others remain sitting, half expecting the singer to come back. Instead Jerry Kellert comes on as the houselights go up. He has the official verdict: "she could have cancelled, but she wanted to come out and give you what she had. That's it. She'll come back some other time and make it up if you still want her." The applause is half-hearted, but no boos are heard. "You have to take her word," says a junior named Sal. "With her type of music, I could see how she could strain her voice." As the gym empties, Kellert takes me, a handful of reporters from the college newspaper, and a young man from a local radio station back to the locker room that Melanie is using as a dressing room. The singer is sitting on a bench, hugging her knees. The radio man tells her John Lennon and his wife, Yoko, are to appear in a demonstration for legalised pot in Albany tomorrow . . . will Melanie join them? She says no, but that she feels pot should be legalised. Then one of the college kids asks about her latest hit, "Brand New Key." Is it representative of the kind of music she's into now? Melanie looks up at me. "See what I was telling you yesterday'' she says. What Melanie had said to me when I saw her yesterday was "Because the song is light-hearted and bouncy--"I've got a brand new pair of roller skates" it goes, "you got a brand new key"-—and I recorded it in a high voice, 1 got criticised. By underground FM heavies you know. But uh, a lot of people thought it had a nice, funny, sort of campy attitude. Its Just that I wrote it. I'm sure if, uh, Paul Simon had written it people would say, 'Terrific'--you know, 'Why not?' Uh, I think there's a lightness and a cuteness that they sort of attach to a girl singing words like that. If I'd recorded 'Me and Julio down by the Schoolyard' (a Simon hit), I'm sure they'd say, 'Ah, sold out again.' " That discussion yesterday had led me to ask Melanie what she meant by selling out. Her answer: "I don't know. 1 guess selling out is to deliberately go into a studio and say, I'm here to cut a hit record and get the bread.' 1 think 'Brand New Key' was something honest . . . not contrived." Now, tonight, sitting cross-legged on the locker-room bench, Melanie merely tells the college journalists that 'Brand New Key" was something she did, and something she should be able to do. Then, follows a discussion of the abortive concert, and Melanie promises the college journalists she would come back. "I have to' she says. "I didn't give you a concert. But if I had, it would've been a good one." The local press leaves, and Melanie wanders around the cavernous locker room, her hair dank against her cheeks, her shoulders hunched. She looks very small. "Look what they done to my song, Ma,' go the lyrics to one of Melanie's really big hits. "Well, they tied it up in a plastic bag/ Turned it upside down, Ma/ Look what they done to me song." Melanie's music goes from lush to lively. The words—strong on satire, too evocative to be called pop—have rhythm and imagery, and range in subject matter From animal crackers and roller skates to peace and pain. Her voice is warm rather than polished; it has an earthly quality. And Melanie lives her songs. Generally, she gets good reviews. COSMOPOLITAN'S Nat Hentoff sums up by saying, "She's a talent." About the only outstanding exception to her favourable notices was a rap in Life magazine a couple of years ago by a critic who went pyrotechnical with adjectives at the expense of Melanie's ability, appearances and audience. "I mean he just called me names," she says. "I sat numb for days after that." As Melanie remembers, she and her husband had taken the writer, who had given the impression he was doing a profile, to one of her concerts: "I didn't know he was doing a review." Not that Melanie's promoters haven't done some plastic baggie work of their own on the singer's image. Take the candle-lighting shtik. Or the double-record album that can be made into a decorative box. Or the official fact sheet that gives you the time, as well as date of Melanie's birth, and discloses that her sixth album, Gather Me, was "twenty-four years in the making.' In classic fan-magazine style, the fact sheet also confides that Melanie 'favours organic living, lives life with great enjoyment, treasures her secret hours." One fact that the sheet does not go into, however, is the difficulty a would-be profiler will have in connecting with Melanie, or even making more than the most ephemeral contact with anybody responsible for her whereabouts. In my case, the anybody I tried to reach was: Kellert, who once represented the singer for the William Morris agency and is now vice-president of her husband's Yew York-based music company, Schekeryk Enterprises. After weeks of phone calls, I felt triumphant in finally keeping Kellert on the line for maybe just a minute-a memorable sixty-second conversation in which he assured me that "this is rock and roll. Harvey, lt.'s all f--cd up . . . but I've l managed for you so spend tomorrow afternoon talking to Melanie." Which brings us to the day before the Sienna concert. Our meeting ground, a suite in the elegant Hotel Pierre, where the Schekeryks make their home when in New York . . . and where Melanie, wrapped in a shirt made from an Indian scrape and a Ukrainian shirt given her by her mother-in-law, stands out among all the patrician luxury like a red rose in a bed of watercress. This erstwhile middle-class kid who is now incorporated talks to me about teen-age experiences that seem far removed from today--not only in time but in substance, Like her running away from hone in Long Branch, New Jersey. The break-up of her parents' marriage (she now tries to see each parent, as well as eighteen-year-old sister, as often as possible).. Her mother being a band singer and therefore Melanie always having had music in her life. The girl studying pottery at a crafts school in North Carolina, then taking up acting at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York Finally, at the age of eighteen, being discovered by a team of music publishers named Hugo and Luigi, who signed her to a contract as composer. It was what you might call a modest beginning. "I hardly made enough money to pay for bus fare into New York," Melanie tells me. "So to appease me a little, the bosses gave me an office. A writing room. And, uh I had a bathroom key. It was my big thing --to have a key to a ladies' room in New York City." When Hugo and Luigi got involved in writing a Broadway show, they hired a young man named Peter Schekeryk to help with their music-publishing company. Eventually, Peter and Melanie left the firm, and he became her manager. About four years ago, she wrote and recorded "Candles in the Rain,"' her first genuine hit, soon after, she says. "The money got crazy, I lost control financially and I guess that's when I started knowing I was successful." Melanie and Peter have been married three years now, and lived together for four years before that. "I never felt guilty in any way," she says. "Rather than being a rebellion of any kind, is was, uh, just something that happened. I was very happy just living with Peter. But even though this is a very freethinking kind of business, society isn't so freethinking. There were times when it was really uncomfortable checking into hotels, and. uh, travelling together. So it was like, 'Why bother?' You know, 'Let's get married' The piece of paper doesn't really mean anything to me. It really doesn't. it was just, 'Why hassle'" Melanie bites her lip in thought: "You know what it is, too? The people around you don't think of it as being legitimate . . . there's a light on you. People who knew we were just living together thought, well, it's only temporary." A few minutes later, we discuss sex and love. "I believe there's a whole picture ' Melanie says "I see my life—I see whatever I'm doing--as a big circle, you know, and there's a whole feeling that, uh, I want to balance myself in the centre, And I think there's a little piece there that's sex, and if it's not right, then it can become an obsession. And if it is right, then it just completes the whole circle." If there is a theme running through Melanie's lyrics, she thinks it has to do with unity, and with people tolerating each other. As she says, "I don't write too much on a personal love-affair thing." But does she believe in love? "Yes. As a matter of fact, I'm really a romantic. I'm looking for the uh, everlasting love affair that'll end all love affairs in the whole world."

"No," she says. "I don't think I do." "How does Peter feel about that?" "I think he knows how I am.-' Melanie pauses, and then laughs. "I don't know what that means, really," she says. But you're happy?" "0h, yeah," says Melanie, then she tells me she and Peter are faithful to each other, but "there's something that is not the excitement thing that's always at the beginning." She is equally frank about drugs. "Well, listen," she says. "I wonder about drugs. I really do. For me, it's a very bad thing. If I have the desire to use drugs now, ilk's a sign of me wanting to hurt myself. And it's a sign for me that something's, uh, wrong. And yet, I know that the psychedelic drugs have helped a lot of people—people who've just sort of been stuck in themselves. And this sort of brought them out. Of course, maybe they go back to the same level " Has Melanie ever been deeply into drugs? "I didn't lose control, hut I did have a dependency I had a dependency on speed, and it's horrible. It really is the worst." She tells me she stopped using speed about five years ago: "It was terrible. Listen, I couldn't go to sleep at night. I'd, uh, have to take something else to go to sleep. It was insane. I was living on one kind of pill after another." Melanie describes her going off pills as both gradual and fortunate: "I have this tendency—uh, this self-sacrificing thing in me. I don't know where it comes from or why I have it. But there're times when I won't eat all day, and I'll drink coffee, and that leaves you very low. There are times when I want something to, uh, drain myself. But I don't even smoke pot anymore. It just vegetates me. I'm nothing with it. And anyway, I'm not good at smoking anything. I have bad lungs. I don't feel the least bit embarrassed saying no thank you anymore." So what does Melanie do, then, to, in her words, "open me up creatively"? Well, she looks "for things that take out the stoppers. Like dunking a little wine occasionally, and meditating. A lot of exercise. And I do yoga. And eat a natural diet." She describes a natural diet as trying to "eat organic" —lots of fruits and vegetables, but meat only two or three times a week. "I'm trying to find a balance," she says. Meanwhile, the pace is dizzying. Melanie and Peter own a house on a three-acre hillside in Lyncroft, New Jersey, but rarely live there, because most of the time they're on the road. Melanie tells me she would also like to act, but has turned down several movie offers: 'They were lots of commune pictures where they wanted me to play the little, uh, ingénue who runs off to Canada with her boyfriend. Anybody can play those parts. I want something with life and a sense of humour and some wit--something that's not, uh, self indulgent and self-pitying." Does she ever worry about becoming make-believe? "I know exactly what you mean," she says. "Sometimes, I feel like I invent every situation I'm in. Either I invent it, or somebody invents it for me." But overall, Melanie feels satisfied with her success: "The way it happened, and the time that it took, was just right. I feel like a healthy carrot that came out from the seed and just grew for the right amount of time, and they, uh, watered it—I feel healthy about what I'm doing." It's hard to think of Melanie as a carrot, but everybody to her own image. A final question: "What's the worst thing anybody could say about you?" 'That I wasn't honest,' says Melanie Safka Schekeryk, "or creative. That I was just some puppet that sings And the music goes 'round and 'round . . . The day after Sienna, Melanie cancels another upstate New York College concert. She rests her voice for a week, then goes back on the road to do a campus date in Pennsylvania. After that, she plays a club in Los Angeles. When I last check, Melanie is in London making a TV show. Perhaps the appearance will include her song Ring The Living Bell ' As one verse goes, "I'm not a magic lady/ But I want to sing to help the light/ Descend on the earth today/ Became it's gonna get dark tonight/ Sing for light, ah/ Sing for living light;" Or, to quote Simon and Garfunkel, "Sail on

silver girl." |

||

|

* Copyright © 1970 by Abkco Misc Inc.

Used by permission. All rights reserved. International Copyright secured. + Copyright ©1970 Kama Rippa Music and Amelanie Music. All rights

reserved #Copyright © Paul Simon 1969 Used by

permission of the publisher -Copyright © 1971 Neighborhood

Music Publishing Corp. |

||

"You're not sure you

have it now?"

"You're not sure you

have it now?"